Archives

PITUITARY

THYROID

Endometriosis

ABSTRACT

Endometriosis is a disease in which endometrial glands and stroma implant and grow in areas outside the uterus. The disease has a multi-factorial etiology including genetic and environmental factors. Exposure to ovarian hormones appears to be essential. Estrogens stimulate ectopic endometrium growth and aberrations in estrogen signaling have been associated with the disease. Caucasians appear to be more likely to suffer from endometriosis than African Americans or Asians. There is also an increased prevalence in taller women and those with a lower BMI. Genetic factors contribute to approximately 51% of endometriosis risk. Patients with an affected first-degree relative have an approximate 7 to 10-fold increased risk of developing endometriosis.

The prevalence of endometriosis ranges from 2-50% of reproductive aged women. The morbidity associated from endometriosis is great, as it can cause both chronic pelvic pain and infertility. In women with infertility, the prevalence ranges from 20-50%. Endometriosis is present in 71-87% of women with chronic pelvic pain.

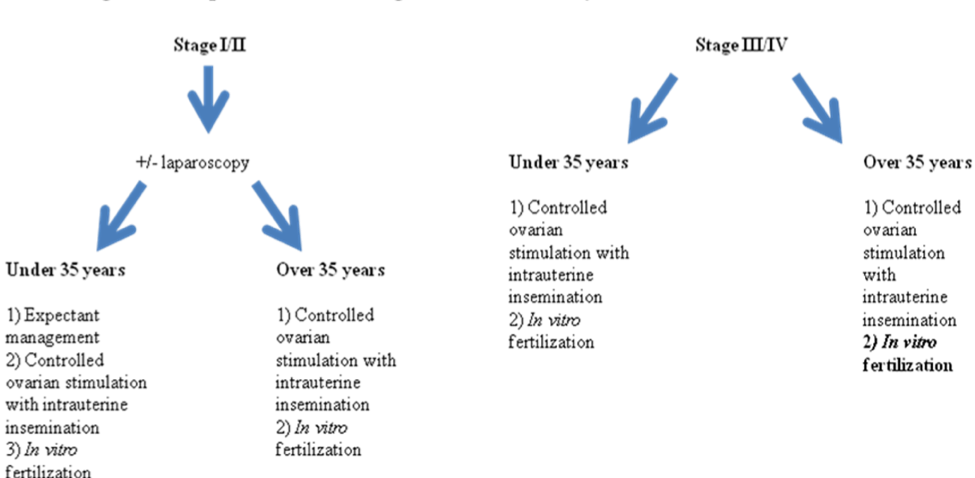

In the treatment of infertility associated with endometriosis, the age, history, health status, physical exam, and wishes concerning treatment should be weighed. There are certain situations where surgery may be indicated for the treatment of infertility associated with endometriosis. Controlled ovarian stimulation with IUI or IVF is often indicated.

DEFINITION

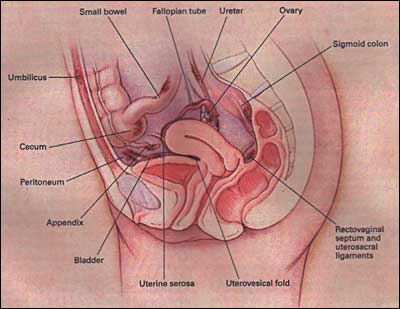

Endometriosis is a disease in which endometrial glands and stroma implant and grow in areas outside the uterus (Fig. 1). The most common place to find implants is in the peritoneal cavity (involving the ovary, cul-de-sac, uterosacral, broad and round ligaments, fallopian tubes, colon, and appendix), but endometriosis lesions have occasionally been found in the pleural cavity, liver, kidney, gluteal muscles, bladder, abdominal scars, and even in men (1).

Figure 1.Common locations of endometriosis within the pelvis and abdomen. (Reprinted by permission from the New England Journal of Medicine 2001. Olive DL, Pritts EA. Treatment of Endometriosis. Vol. 345:267).

There are three typical types of endometriotic lesions: 1) superficial peritoneal and ovarian implants, 2) endometriomas (ovarian cysts that are lined with endometrioid mucosa), and 3) deep infiltrating endometriosis (complex nodules comprised of endometriotic tissue, adipose tissue, and fibromuscular tissue) (2,3). The anatomical location and inflammatory response to these lesions are believed to account for the symptoms and signs associated with endometriosis.

ETIOLOGY

Classically, three theories exist to explain the etiology of endometriosis; 1) Sampson’s theory, 2) Meyer’s theory, and 3) Halban’s theory. The most often quoted theory, and to date the one supported by the most evidence, is Sampson’s theory of transplantation and implantation. This theory stemmed from observations made during surgeries in the 1920’s that many women shed endometrial debris through their fallopian tubes into the peritoneum during menstruation (4). Not only has viable endometrial tissue been found in the fallopian tubes and peritoneal fluid of women, but in humans and other animals, endometrial tissue will grow if placed ectopically. Further supporting this theory, endometriosis seems to occur most commonly in the gravitationally dependent parts of the pelvis (5). Finally, the incidence of endometriosis is significantly increased in patients with mullerian anomalies or genital tract obstructions, both which increase the likelihood of retrograde flow (6). One problem with this theory is that retrograde menstruation has been shown in 76-90% of menstruating women, which is much higher than the prevalence of endometriosis (7,8). This discrepancy suggests that additional factors beyond the presence of ectopic tissue are needed to establish the disease, such as the amount of endometrial debris that reaches the peritoneal cavity, the immunocompetency of the woman to clear the debris, and the molecular abnormalities/properties inherent in the ectopic tissue. Meyer’s theory (9) suggests that metaplasia of the coelomic epithelium is the origin of endometriosis. This theory is logical, as cells from both the peritoneum and endometrium are derived from a common embryological precursor: the coelomic cell. However, this has been a difficult theory to support scientifically. If this postulate were correct, one would expect much higher rates of pleural endometriosis than are observed. Halban’s theory is one that suggests that distant lesions are established by the hematogenous or lymphogenous spread of viable endometrial cells. Although this metastatic theory explains rare endometriotic lesions in the brain or lung, it does not explain the gravitationally-dependent location of most foci of endometriosis. Sampson’s transplantation and implantation theory is the most widely accepted, but most researchers agree that it grossly simplifies the disease process. Whilst retrograde menstruation can transplant tissue fragments into the peritoneal cavity, the cells themselves must escape apoptosis (10), adhere to the underlying peritoneum (11,12), degrade the underlying extracellular matrix (13), generate a new vascular supply (14), and evade the immune surveillance system (15) in order to survive. Clear molecular differences exist between endometriotic lesions and eutopic endometrium. Secondary to the inflammation associated with endometriosis, there are increased levels of prostaglandins, chemokines, and cytokines, such as interleukin-1ß, intlerleukins-1, 6, 8 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which are thought to enhance the adhesion of endometriotic implants to the peritoneal surface. These are associated with overproduction of prostaglandins, cytokines, and chemokines. Proteolytic membrane metalloproteinases, also increased in endometriosis, promote implantation. Angiogenesis and apoptosis are also altered in endometriosis in favor of survival of the implant. Granulocytes, macrophages, and natural killer cells are attracted by the increased monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, interleukin-8, and RANTES (regulated upon activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted), present in endometriosis. These inflammatory mediators accumulate in endometriotic tissue by autoregulatory positive feedback loops (16). Erythrocyte breakdown from endometriotic lesions is internalized by macrophages and the non-protein-bound catalytic iron increases the production of reactive oxygen species, thereby perpetuating peritoneal damage and inflammation. Studies have found no association between the oxidative stress and antioxidants such as Vitamins A and E (17), but the association between Vitamin D and endometriosis is more complex. Several studies suggest a role for Vitamin D and its metabolites as local autocrine and paracrine agents involved in endometriosis etiology and pathology (18-20), but the exact mechanism has yet to be elucidated (21). While steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1) is present in ectopic endometrial tissue, it is not found in the eutopic endometrium. SF1 is involved in estradiol synthesis. The increased amount of estradiol seen in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis increases local cyclo-oxygenase -2 (COX-2) activity, resulting in stimulation of prostaglandin E2 formation, which upregulates aromatase activity, resulting in additional estradiol to perpetuate the symptoms and lesions present in endometriosis (16). There is elevated expression of both estrogen receptor α and estrogen receptor ß leading to a downregulation of progesterone receptors (2), ultimately causing the characteristic hormonal profile seen in endometriosis.

DEMOGRAPHY

Endometriosis is diagnosed in women aged 12-80 and the average age at diagnosis is approximately 28. The disease has a multi-factorial etiology including genetic and environmental factors. Exposure to ovarian hormones appears to be essential with the vast majority of the cases found in women aged 20-50. Estrogens stimulate ectopic endometrium growth and aberrations in estrogen signaling have been associated with the disease (2, 22). Caucasians appear to be more likely to suffer from endometriosis than African Americans or Asians (23). There is also an increased prevalence in taller women and those with a lower BMI (24). Genetic factors contribute to approximately 51% of endometriosis risk. Patients with an affected first-degree relative have an approximate 7 to 10-fold increased risk of developing endometriosis (25, 26). Several at risk loci have been identified: WNT4, CDKN2B-AS1, and GREB1 (27,28). WNT4 encodes for gene products that are important for the development of the female reproductive tract and for steroidogenesis. The CDKN2B-AS1 gene is located in an enhancer region and includes a gene cluster that encodes tumor suppressor proteins such as p15, p16-NK4a, and p14ARF. GREB1 encodes an early-response gene in the estrogen receptor regulated pathway (27,28). Risk factors for this disease include nulliparity, early menarche, and frequent or prolonged menses. Protective factors include pregnancy, menopausal status, multiparity, and periods of lactation (29).

PREVALENCE

The prevalence of endometriosis ranges from 2-50% of reproductive aged women. Unfortunately, this number is widely disparate depending on the study. In women with infertility, the prevalence ranges from 20-50% (30-33). This may be due to the fact that endometriosis plays a causative role in infertility, but it also may be due to a diagnostic selection bias, as women with infertility often undergo laparoscopy as part of their clinical evaluation. Endometriosis is present in 71-87% of women with chronic pelvic pain (34-36). Between the years 1965 and 1984, endometriosis increased from 10% to19% as the primary indication for hysterectomy in the USA. Interestingly, this happened during a time in which a trend towards more conservative therapies as treatment modalities for endometriosis occurred (37). This finding suggests a true increase in the incidence of the disease. Varying theories have been proposed to explain this increase, including a delay in childbearing, declining use of oral contraceptives, and exposure to environmental toxins such as dioxin as a causative agent (38). A recent study involving mice has demonstrated that bisphenol A (one of the highest volume chemicals produced worldwide) is able to elicit an endometriosis-like effect in mice who were prenatally exposed (39). Human studies, however, are equivocal (40-42). Other studies have found higher phthalate concentrations in women with endometriosis than those without the disease (40, 42-48).

SYMPTOMS

Pain

The most common symptom for women who have endometriosis is pelvic pain, although the pathophysiologic mechanisms are not well understood and many women with endometriosis may not have this complaint. The pain is most often cyclic, but may also be chronic in nature. The pain usually begins just before menses and continues throughout the duration of menstrual flow. Dysmenorrhea and deep dyspareunia are the most common pain complaints with 80% and 30% prevalence, respectively (49-51). Dysuria, dyschezia, and intermenstural pelvic pain are less common and are associated with bladder or bowel lesions. The pain may also be perceived in musculoskeletal regions, such as the flank, low back, or thighs. The heterogeneity of the disease process makes it difficult to ascertain the exact etiology of the pain. Actively bleeding lesions can certainly cause discomfort. Pain may also be produced by the production of inflammatory mediators and neurologic stimulation. It is likely that different types of lesions cause pain through differing pathways. Early papular lesions contain higher levels of prostaglandins than older lesions. These prostaglandins may activate afferent neuronal pathways. Lesions deeply penetrating the peritoneum also have an increased propensity to cause pain, probably by direct irritation and invasion of pelvic nerves. Endometriomas may cause a mass-effect, which can result in the perception of pain. Adhesions and fibrosis cause pain by compromising the blood supply to certain neuronal plexi, or by placing small nerves on tension (52). In addition to the perturbation of nerve fibers by the lesions, studies have demonstrated that neuronal fibers are present in endometriotic lesions found on the ovaries. A nerve growth factor (a substance important for the maintenance of sensory nerves), S 100 (a neurotrophic factor), and PGP9.5 (an immunoreactive nerve fiber) have all been demonstrated in these lesions, which may contribute to the generation of pain (53). Other studies have shown that there is an increased amount of nerve fibers present in the endometrium in patients with endometriosis (54-57). The significance of these observations remains to be determined, but it has been suggested that the presence of nerve fibers in the endometrium may be used to diagnose endometriosis. With a chronic inflammatory environment in endometriosis, it is theorized that there may be a feedback cycle that promotes nociceptor sensitization with activation and neogenesis of sensory nerve fibers resulting in hyperalgesia (58). Finally, endometriosis can be associated with increased pain perception secondary to abnormal modulation of nociceptive input and an increase in intensity of neuronal signaling to the brain (59-61). Macrophages in the peritoneal fluid in women suffering from endometriosis are increased in concentration and activity (62). As discussed previously, macrophages are part of an inflammatory cascade, which perpetuates the sensation of pain, as does the constant elevated production of prostaglandins.

Infertility

The next most common symptom is that of infertility. Women with moderate and severe endometriosis, particularly those in which the ovaries and oviducts are involved with adhesive disease, have decreased fertility rates. It is theorized that this stems from the mechanical obstruction between the ovary and oviduct, with subsequent failure of gamete transport into the tubal ampulla. Many women with moderate to severe endometriosis have undergone operative management for their disease ; as a result, they may have decreased amounts of functional ovarian tissue and thereby suffer from decreased fecundity. Interestingly, women with only minimal or mild disease may also have decreased fertility when compared to those without clinical evidence of endometriosis. It remains controversial whether endometriosis is the cause of this subfertility. Some studies report that even minimal stage disease is associated with decreased fecundity, while other studies report no effect on fertility and pregnancy outcome (63, 64). The monthly fecundity rate in normal couples is 15-20%, while the monthly fecundity rate in women with untreated endometriosis and infertility is 2-10% (65).

In addition to the anatomic causes of infertility mentioned above, there are two other major theories that may explain the decreased monthly fecundity rates seen in women with endometriosis: 1) inflammation and 2) a locally altered hormonal profile. The altered cellular immunity results in an increased amount of inflammatory mediators, such as activated macrophages, RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted), interleukins, and tumor necrosis factor in follicular fluid and in peritoneal fluid. This results in a locally hostile, cytotoxic environment, characterized by oxidative stress, that negatively impacts most aspects of reproduction by causing altered folliculogenesis, oocyte degradation, structural DNA damage, decreased spermatozoal integrity, decreased fertilization potential, embryo fragmentation, impaired tubal function, and decreased endometrial receptivity. The altered humoral immunity results in the presence of autoantibodies with the capability of binding to the endometrium and, possibly the oocyte, sperm, embryo, and tube. The presence of elevated levels of steroidogenic factor-1, estrogen, and estrogen receptors in endometriotic cells ultimately leads to a down regulation of local progesterone receptors, and thus, an altered local reproductive hormonal profile (2,16, 66). Altered folliculogenesis has been proposed as one of the contributing factors to infertility. Characteristics of in vitro fertilization cycles in women with endometriosis include a slower follicular growth rate and reduced follicle size. Changes in the cell-cycle kinetics of the granulosa cell that favor an increase in the amount of cells in the S phase and in cells undergoing apoptosis may play a role in this phenomenon. There is a decreased amount of vascular endothelial growth factor present in follicular fluid, which is believed to be responsible for the decreased follicular health and vascularization seen in endometriosis.

Endometriosis has a multifactorial impact on the health and function of spermatozoa. The increased generation of reactive oxygen species seen in women with endometriosis results in the loss of spermatozoal membrane integrity and enzyme inactivation, thereby decreasing the potential for fertilization. Decreased sperm motility, mediated by glycoprotein-130 binding in sperm, is also a result of the negative impact endometriosis has on sperm function. The endosalpinx in women with endometriosis tends to bind spermatozoa more tightly, resulting in a decreased number of available spermatozoa. A decreased ability of spermatozoa to bind to the zona pellucida is evident in patients with endometriosis, resulting in impaired fertilization. Taken together, it is clear that endometriosis has a negative impact on the spermatozoa (16).

There are a few proposed mechanisms by which endometriosis impairs implantation. Explanations include the delayed histologic maturation or the biochemical alterations of the endometrium, both seen in endometriosis. In another mechanism, αvβ 3 integrin, an adhesion factor which is normally increased during the optimum implantation window, is decreased or absent in patients with endometriosis (16). Evidence indicates that the eutopic endometrium of women who suffer from endometriosis is abnormal in its expression of implantation-associated proteins, e.g., complement protein (C3) (67), IL-6 (68), HOX A 10 and 11 (69), and b3 integrins (70). The zona pellucida of the embryo is compromised by the cytotoxic effects of the reactive oxidative species, which may also lead to impaired implantation (16).

Other Symptoms and Associations

Other symptoms of endometriosis can include abnormal menstrual bleeding, diarrhea, constipation, and chronic fatigue. There are elevated rates of autoimmune diseases, including hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, and multiple sclerosis in patients with endometriosis. Reports of allergies, asthma, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia are also more common in women with endometriosis than in women in the general US population (71).

PHYSICAL EXAM FINDINGS

Unfortunately, due to the diffuse and often varying nature of endometriotic lesions, the physical examination is typically unrevealing. The findings are variable and of limited precision in either localization or diagnosis of endometriosis. However, tender nodules may be palpable along the uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, or within the cul-de-sac, especially if the examination is performed just before menses. The astute clinician can appreciate pain or induration in the vicinity of otherwise non-palpable lesions, most commonly in the cul-de-sac, along the uterosacral ligaments, or rectovaginal septum. The clinician may also appreciate uterine or adnexal fixation or a tender adnexal mass. Because much disease is found in the dependent areas of the pelvis, it is critical to perform a systematic rectovaginal examination. In that way, the practioner is assured of evaluating the cul-de-sac and uterosacral ligaments as well as the adnexa (72).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of endometriosis includes pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-ovarian abscess, ectopic pregnancy, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, adenomyosis, pelvic adhesions, uterine fibroids, chronic or acute endometritis, ovarian neoplasms, musculoskeletal disease, gastrointestinal neoplasms, appendicitis, and diverticular disease.

DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES

Laparoscopy with visualization of lesions is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Dogma states that a biopsy of the lesion is the only way to truly confirm a disease diagnosis. For those surgeons trained in advanced laparoscopy, direct visual recognition of endometriosis also allows treatment to be instituted immediately. Laparoscopy is preferred over laparotomy as it provides visualization of the entire abdomen and pelvis at magnified views, has less morbidity than laparotomy, and carries a decreased risk of adhesion formation (73, 74). One of the major limitations of diagnostic laparoscopy for pelvic pain is the assumption that those lesions seen (or not seen) directly correlate with the symptoms of pain. Attempts to develop noninvasive radiological imaging techniques as diagnostic tools for endometriosis have been compromised by lack of specificity. Computed tomography was used initially to diagnose endometriomas in the setting of adnexal masses. Unfortunately, not only was it difficult to distinguish between benign versus malignant masses, it was often impossible to distinguish adnexal structures and loops of bowel (56, 57). Hence, this modality is of little value for this purpose. Transvaginal ultrasound is considered the first-line imaging modality. The typical ultrasound appearance of an endometrioma is a homogeneously hypoechoic unilocular cystic mass with low-level internal echoes and a ground glass appearance. Occasionally, endometriomas may be multilocular, though they typically have fewer than five locules. The vaginal probe can further be used in the evaluation of endometriosis by helping to determine the mobility of pelvic organs. For example, if the ovary appears to be affixed to the uterus, the probe can be used to apply pressure to the ovary. If the ovary does not move with the applied pressure, one can conclude that there are adhesions preventing such movement (75).

The addition of cystoscopy, colonoscopy/ sigmoidoscopy, renal ultrasound, intravenous pyelogram, or barium enema should be considered if there is cyclic bowel/bladder dysfunction or back pain to rule out ureteral, bladder, or rectal involvement of deep lesions or other malignancy. Because of the broad range of symptoms that are included in endometriosis, a multi-disciplinary approach is often required for diagnosis and management (76-82). At present, magnetic resonance imaging is the best imaging for identifying endometriosis, and it can identify implants as small as 3mm in size (83, 84). It also has been shown to differentiate benign from malignant lesions, with excellent sensitivity and specificity, and is the method of choice for preoperative evaluation of any adnexal mass (85, 86). Because of the large disparity in cost of an MRI versus a transvaginal ultrasound, physicians may resort to using an MRI in cases of ultrasonographically indeterminate pelvic masses (3). Much research has been devoted to discovering a serum marker that will allow diagnosis and monitoring of treatment, to no avail. Monoclonal antibodies raised against a high molecular weight ovarian cancer epithelial cell antigen, CA-125, have been used as a biochemical marker of endometriosis. Moderate and severe endometriosis is associated with elevated levels of CA-125 in the peripheral blood (87). Unfortunately, this marker is relatively non-specific, being increased in ovarian cancer and other gynecologic malignancies (fallopian tube carcinoma, germ cell tumors, adenocarcinoma of the cervix, sertoli-leydig cell tumors), benign gynecologic conditions (benign pelvic neoplasms, adenomyosis, pregnancy, pelvic inflammation), liver disease, colitis, colon cancer, diabetes, congestive heart failure, some autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders, ascites, breast cancer, lung cancer, and even during menstruation of women without any disease. Although it may help define progression of disease in individual patients, its diagnostic utility is limited. Studies have reported an increased density of nerve fibers exist in the eutopic endometrium of patients with endometriosis, but there is controversy as to whether aberrant innervation in the endometrium is a reflective of gynecologic pathology in general (53, 90, 91, 94, 95) or a specific feature of endometriosis (55, 92-97). It was once thought that endometrial biopsies may prove to be useful in the diagnosis of endometriosis, but recent studies demonstrated the presence of neuronal markers in endometrial pipelle biopsies from women both with and without endometriosis (98).

CLINICAL APPEARANCE

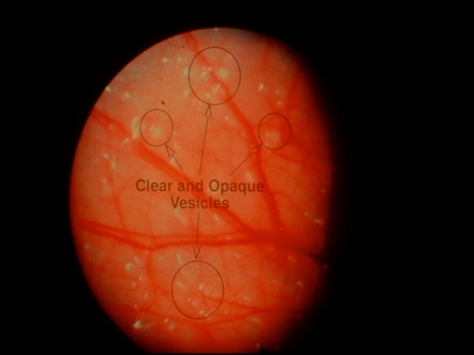

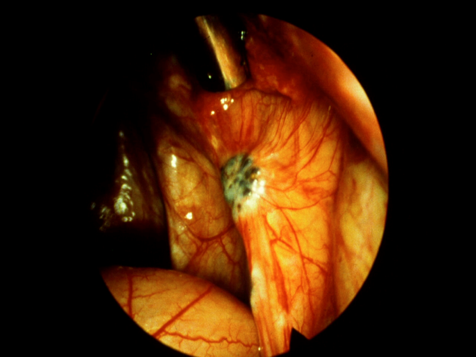

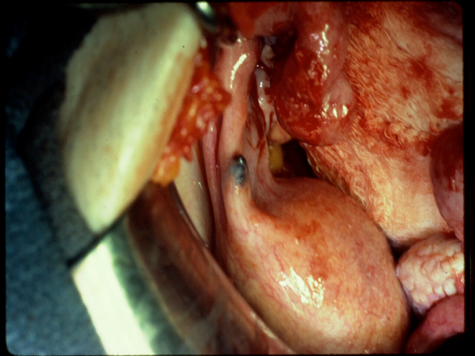

Grossly, peritoneal endometriosis can take on many visual appearances. Classically, it was taught that endometriosis implants were blue-black “powder-burns” or “mulberry lesions” of the peritoneum. More recently, several stages of implant development have been appreciated, each with a corresponding appearance. Early, active lesions can appear as papular excrescences or vesicles, and can range in color from clear to pink, or bright red (98). About a third of these lesions are in phase with the eutopic endometrium, and have a tendency to spontaneously grow and regress, suggesting a fluctuation of proliferation in association with the cyclic hormone production during the menstrual cycle (99). Advanced, active lesions are associated with inflammation, fibrosis and hemorrhage, and take on a more classic appearance identifiable at surgery. These lesions can express a myriad of colors, from black to brown, purple, red, or green. These are due to the presence of heme degradation products as the foci undergo hemorrhage and fibrosis. Dormant and healed lesions take on either a white or calcified appearance, and represent remnants of glands embedded in fibrous tissue (98). The surface of peritoneum may also be puckered or contain windows (Allen-Masters windows). A specific manifestation is the endometrioma or chocolate cyst. These ovarian cysts gained their moniker by the characteristic chocolate syrup appearance of their contents often seen at rupture. They arise after implantation of ectopic endometrial tissue and subsequent invasion into the normal ovarian cortex. The cell types present in these cysts include endometrial epithelium, both as glands and flattened cells, endometrial stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages. In some cases, ciliated cells, similar to those of oviduct epithelium, have been observed (56 100). Under scanning electron microscopy, microscopic lesions have been found in the normal appearing peritoneum of women with and without endometriosis (101). The clinical significance of these findings is presently unknown, but the existence and potential tissue activity in these occult lesions may contribute to the recurrence/occurrence of endometriosis or persistence/recurrence of symptoms in women even after successful ablation or excision of visible lesions.

Fig 2a

Fig 2b

Fig 2c

Figure 2. Intraoperative appearance of endometriosis. (a) The vesicular appearance of early, active lesions. (b) Peritoneal windows. (c) The characteristic blue-black appearance of more advanced, active implants.

HISTOLOGY

Although the histopathologic finding of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma is the sine qua non for establishing the diagnosis of disease, only about 50-70% of presumed endometriosis specimens fulfill these criteria. Many specimens harbor fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and/or hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Most pathologists and clinicians accept these latter findings as highly suggestive of disease status. Eutopic endometrium and endometriotic implants are histologically similar, but as mentioned previously, they are functionally, biochemically, and hormonally different from each other.

CLASSIFICATION

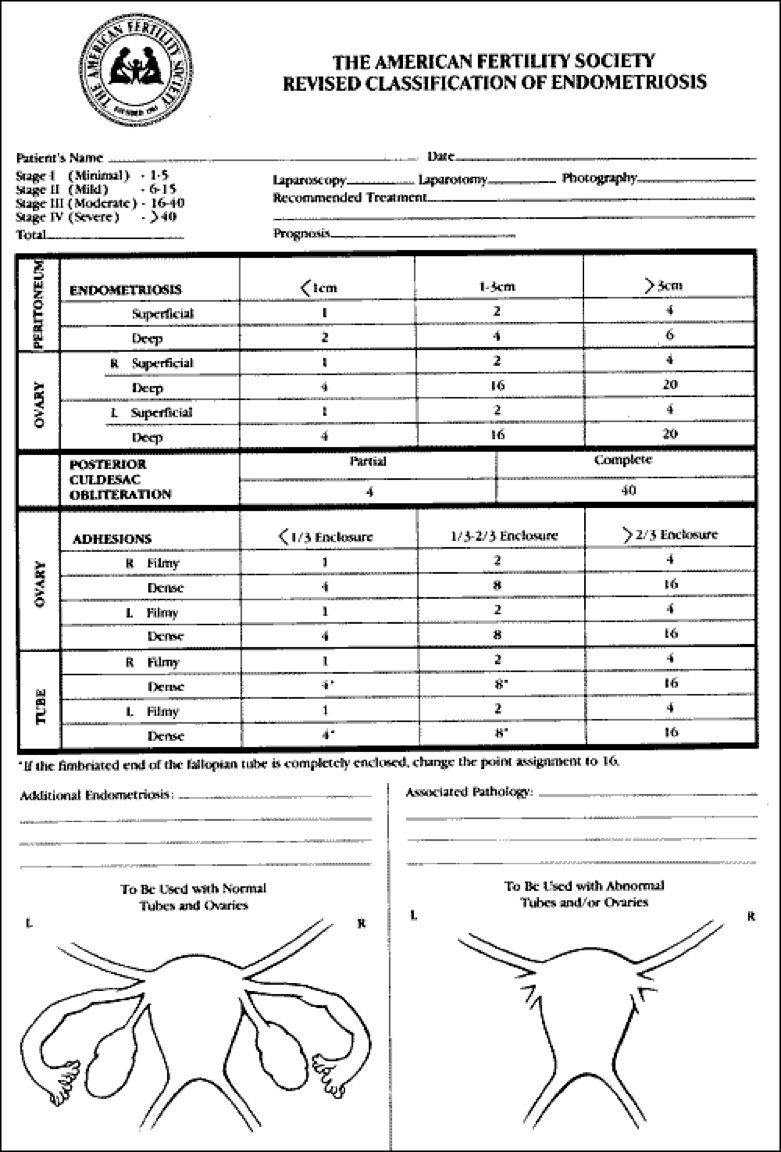

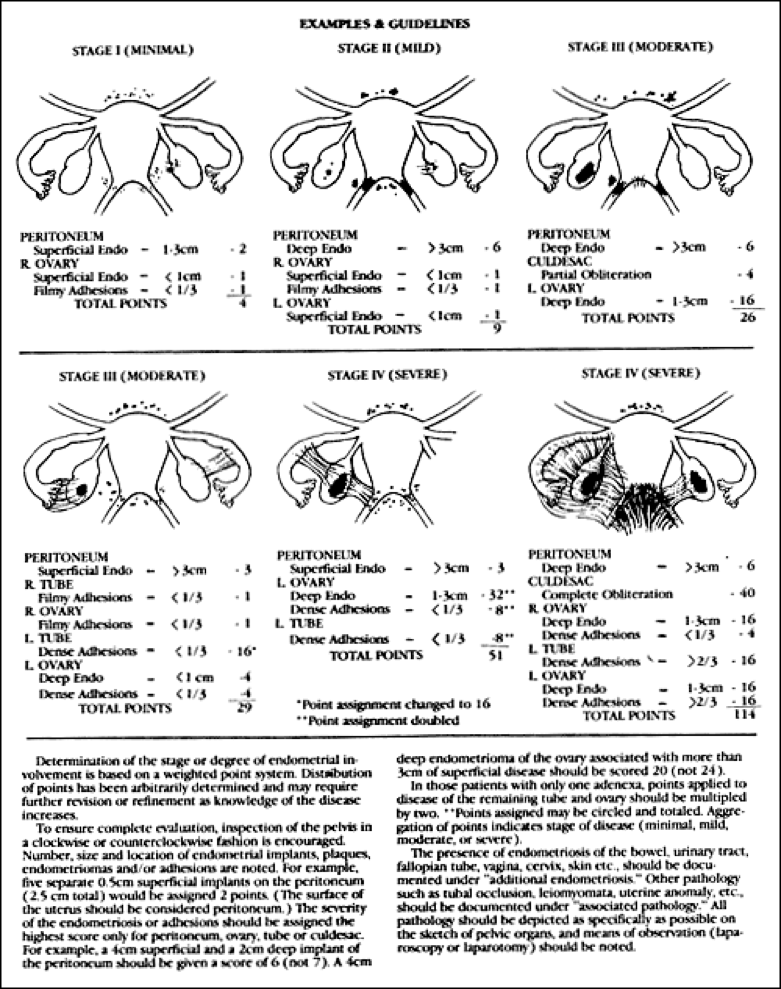

The scheme most widely used to classify the extent of disease is the one derived from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), revised in 1996 (103)(Fig. 3 and 4). This scheme designates disease extent based upon the total 3-dimensional volume of endometriosis. Importance is placed upon the size, depth of invasion, bilaterality, ovarian involvement, extent of cul-de-sac involvement, as well as density of associated adhesions. From this system, point scores are assigned and tallied, with scores of 1-15 representing minimal or mild disease, 16-40 moderate, and >40 severe. It is important to note that this staging system was established to predict fertility outcomes and does not correlate with the more common symptom of pelvic pain. Unfortunately, the classification system is not good at predicting which women will suffer from infertility, as infertility may even occur in women with mild endometriosis. Commonly, practitioners classify endometriosis as minimal (isolated small implants), mild (superficial implants <5cm total, only located on the ovaries and peritoneum, no adhesions), moderate (multiple superficial and invasive implants with or without adhesions), or severe (endometriomas), and the classification system by the ASRM is sometimes reserved for use in studies, where standardization of the classification is important. Use of the ASRM classification system should be encouraged, however, because it best describes the full extent and location of endometriotic lesions. It provides clinicians caring for women with endometriosis with a detailed description of the location and extend of disease.

Figure 3. The American Fertility Society Revised Classification of Endometriosis. (Reprinted by permission from Fertil Steril 1985;43:351).

Figure 4. Examples and guidelines for use of the American Fertility Society Revised Classification of Endometriosis. (Reprinted by permission from Fertil Steril 1985;43:352).

TREATMENT

Treatment for endometriosis differs depending on the symptom being targeted and whether or not the patient is trying to become pregnant in the near future . Treatment is either aimed at pain reduction, fertility restoration, or evaluation and treatment of a pelvic mass. Unfortunately, there are few treatment options for those who desire both fertility in the near future and the treatment of pelvic pain. However, sometimes pregnancy will temporarily relieve the pain associated with endometriosis.

Pain

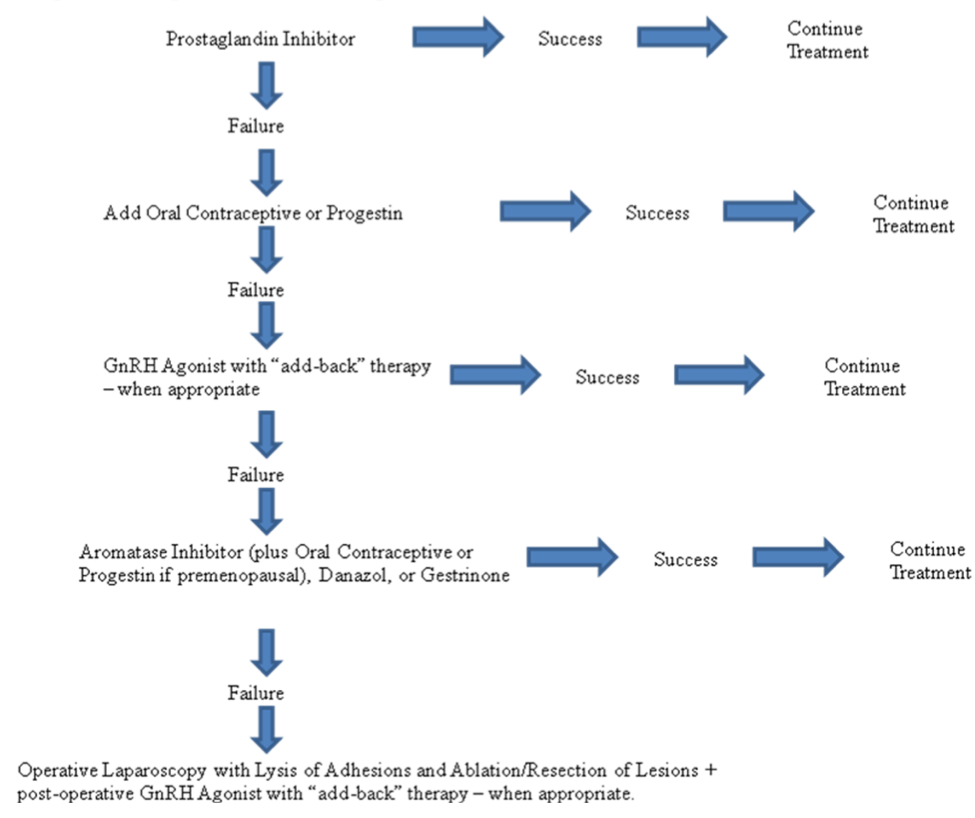

Pain is the most commonly reported symptom of endometriosis, an estrogen-dependent condition characterized by chronic peritoneal and pelvic inflammation. Since endometriosis is a chronic disease, it would be most beneficial to use agents that can be safely used long-term. Dysmenorrhea is one of the most common complaints in women with endometriosis, so many of the hormonal agents aim to cause amenorrhea. These treatments may also relieve deep dyspareunia, non-cyclic pelvic pain, and dyschezia. Hormonal agents may have an additional effect on reducing the nerve fiber density present in endometriotic lesions, which is believed to be one of the factors involved in the origin of the pain caused by endometriosis (104). Oral contraceptives, progestins, danazol, gestrinone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and GnRH agonists are all supported by clinical trials showing approximately equal benefit over placebo (Fig. 5). These hormonal agents create a hypoestrogenic (GnRH agonist), hyperandrogenic (danazol, gestrinone) or hyperprogestogenic (oral contraceptives, medroxyprogesterone acetate) state that suppresses endometrial cell proliferation. Their side-effect profiles and costs lead one agent to be preferred over another. However, once the agent is discontinued, the symptoms tend to recur. A definitive diagnosis of endometriosis can only be made with surgery. If there is sufficient clinical suspicion of endometriosis, it is reasonable to try empiric therapy with a single agent or a combination of agents. Oftentimes, the pain will improve and surgery can be avoided.

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) has been used for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain for several years. Its efficacy in reducing symptoms of pain is well-established and works by decreasing retrograde menstruation, inducing a pseudo-pregnant state and causing decidualization and subsequent atrophy of eutopic and ectopic endometrium. Advantages include a mild side-effect profile, several combinations from which to choose, and the choice of cyclic or continuous administration. However, not all women are candidates for the use of COCPs. COCPs are FDA approved for contraception, but they are used off-label for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

There are many progestins (synthetic derivatives of progesterone) that have been used to treat endometriosis-associated pain. Examples include norethindrone (norethisterone), medroxyprogesterone, and levonorgestrel. There are several routes of administration. They do not contain estrogen; thus, they are believed to be safer for use in women who have a contraindication to estrogen. Norethindrone acetate is a progestin that is taken orally and is initiated at the dose of 5 mg/day and can be increased by increments of 2.5 mg to achieve amenorrhea or to a total dose of 20 mg/day. Side effects include break-through bleeding and breast tenderness. Favorable effects on bone-mineral density (short term) and lipid metabolism have been reported (105). Norethindrone acetate is FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Medroxyprogesterone, a 17-hydroxy derivative of progesterone, taken orally, has moderate androgenic activity and minor effects on the lipid profile. The dose may range from 15-50 mg/day. Side effects may include breakthrough bleeding and depression/anxiety. The intramuscular dose or subcutaneous dose of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate is 150 mg given every 3 months. There is concern about the decrease in bone mineral density with long-term use of medroxyprogesterone. However, studies have shown that after discontinuation of this medication, the bone mineral density profile improves. It takes an average of 7 months for menses to return. The abnormal bleeding and lipid profiles are still concerns for long-term use (105). Medroxyprogesterone is FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

The levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device releases 20 µg/day and induces amenorrhea by causing the endometrium to become atrophic and inactive. It has been shown to improve dysmenorrhea, relieve deep dyspareunia, and, as expected, reduce monthly blood loss. Approximately one third of users will develop amenorrhea. Reasons for discontinuation include irregular bleeding, pelvic pain, breast tenderness, and weight gain. There is a 5% expulsion rate and a 1.5% infection rate associated with use of the intrauterine device. Advantages of this system are that it doesn’t induce a systemic hypoestrogenic state and it is effective, without any further medical intervention, for five years. It is currently being evaluated for postoperative use in women who undergo laparoscopy for endometriosis (105). It is not FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain, but it is approved for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

For the relief of pain caused by the deep infiltrative type of endometriosis, a combination of different types of agents may be of benefit. A study with continuous oral ethinyl estradiol 0.01 mg/day with cyproterone acetate 3 mg/day or only norethisterone 2.5 mg/day demonstrated that both regimens substantially decreased dysmenorrhea, non-cyclic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, and dyschezia, but both caused slight weight gain and undesirable changes in lipid profiles. The group treated by norethisterone reported slightly better symptom improvement but also registered additional androgenic side effects (105).

GnRH agonists have been shown to decrease dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and non-cyclic pelvic pain by creating a hypoestrogenic environment. Some agonists are given subcutaneously either once a month at a dose of 3.75 mg or once every three months at a dose of 11.25 mg. The side effects of GnRH agonists include a reduction in bone mineral density and, therefore are not recommended for periods longer than 6 months. Other side effects include hot flushes, emotional lability, vaginal dryness, insomnia, and loss of libido. “Add-back therapy” with a low dose estrogen/progestin combination has been introduced to prevent the loss of bone mineral density and control the other side effects resulting from the hypoestrogenic environment, while continuing to control the symptoms of endometriosis (105). GnRH agonists are FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

GnRH antagonists are newer compounds and avoid the undesirable “flare” caused by the agonists. Unfortunately, they are not as well studied and must be administered subcutaneously at least once a week at a dose of 3 mg (105). More recent studies have looked at oral formations of GnRH antagonists (106). These show promising results in terms of reduced dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain. However, much is still unknown regarding reversibility of adverse outcomes such as decreased bone mineral density and altered lipid profiles. Thus far, it appears that oral GnRH antagonists have less complete suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis compared to GnRH agonists. It may be inferred that hypoestrogenic side effects may be less with GnRH antagonists compared to GnRH agonists; however, studies showed incomplete suppression of ovulation, and pregnancy may still occur with the use of GnRH antagonists (106). Clinical trials are on-going, but currently GnRH antagonists are not FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

Danazol, an oral agent, induces an amenorrheic state by suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, and is characterized by hyperandrogenemia and hypoestrogenemia. The hormonal cyclicity of the menstrual cycle is interrupted, thereby disrupting steroidogenesis and estrogen production from the ovary that leads to the undesirable painful symptoms in endometriosis. Its use is losing favor because of its undesirable side effects. Weight gain, fluid retention, breast atrophy, acne, oily skin, hot flushes, hirsutism, and unfavorable changes in the lipid profile are among the side effects of danazol. Alternative routes of delivery may result in a beneficial relief of symptoms, while significantly reducing the side effect profile. Studies have looked at a danazol-releasing intrauterine device, vaginal ring, or vaginal capsules, but these preparations are not available at this time (105). Danazol is FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

Gestrinone, an oral agent, is a 19-norsteroid derivative that was originally designed as an oral contraceptive. It has the ability to block follicular development and estradiol production by causing both agonist and antagonist effects when bound to progesterone receptors. Its ability to bind to androgen receptors, however, is responsible for its undesirable side effects: an unfavorable lipid profile, weight gain, hirsutism, seborrhea, and acne. Like danazol, this medication is not frequently used (105). Gestrinone is available in many countries for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain, but is not approved for use in the US.

Aromatase inhibitors have recently become part of the armamentarium against endometriosis-associated pain. Aromatase is the enzyme responsible for the conversion of androgens into estrogens, and is normally expressed in granulosa cells, skin fibroblasts, adipocytes, and syncytiotrophoblasts. Although, steroidogenic factor-1 is found in endometriotic tissue, it is not found in eutopic endometrium. Steroidogenic factor-1 activates aromatase gene transcription, thereby increasing the production of estrogen. Because endometriosis is estrogen-dependent, and aromatase is responsible for estrogen production, aromatase inhibitors have therefore been employed to alleviate the painful symptoms caused by endometriosis. Combination therapy of an aromatase inhibitor with a progestin, oral contraceptive agent, or GnRH agonist is recommended in the treatment of endometriosis in pre-menopausal women because of their ovarian stimulatory properties in this population and to prevent pregnancy. Aromatase inhibitors have a tolerable side-effect profile and don’t reduce bone mineral density (105). Aromatase inhibitors are not FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain, but clinical trials are ongoing.

Historically, there has been a well-established role for prostaglandin inhibitors, such as ibuprofen, in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Recently, a Cochrane Review evaluated non-steroidal anti-inflammatory use for the treatment of endometriosis (107). It discovered two studies that met their inclusion criteria. They found inconclusive evidence to show that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents are effective for the treatment of pain associated with endometriosis. Despite this review, prostaglandin inhibitors are relatively safe, have a tolerable side-effect profile, and can generally be taken on a long-term basis by most patients, so they remain part of the first-line therapy for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. However, their use is associated with undesirable and potentially severe gastrointestinal side-effects that may cause them not to be candidates for use in every patient. Motrin (ibuprofen), a commonly used prostaglandin inhibitor is FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

| Figure 5: Options for the Treatment of Pain Associated with Endometriosis | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Agent | Route | Side-Effects | |||||||||||||||||||

| Oral Contraceptive Agents | Oral | Mild nausea, vomiting | |||||||||||||||||||

| Progestins | Oral, Injection, or Intrauterine | Breakthrough bleeding, breast tenderness | |||||||||||||||||||

| Some have unfavorable effects on bone mineral density and lipid profile | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Some have androgenic side-effects | |||||||||||||||||||||

| GnRH Agonists | Injection or Intranasal | Symptoms of a hypoestrogenic state | |||||||||||||||||||

| (hot flushes, mood irritability, vaginal dryness, sleep disturbances, and decreased bone mineral density) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| GnRH Antagonists* | Oral | Symptoms of hypoestrogenic state | |||||||||||||||||||

| (hot flushes, decreased bone mineral density, unfavorable changes in the lipid profile) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Aromatase Inhibitors | Oral | Ovarian stimulation in pre-menopausal women | |||||||||||||||||||

| Danazol | Oral | Weight gain, fluid retention, breast atrophy, acne, oily skin, hot flushes, hirsutism | |||||||||||||||||||

| Unfavorable changes in the lipid profile | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gestrinone | Oral | Unfavorable changes in the lipid profile | |||||||||||||||||||

| Weight gain, hirsuitism, seborrhea, and acne | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prostaglandin Inhibitors | Oral | Unfavorable gastrointestinal side-effects | |||||||||||||||||||

Figure 5. Pharmacologic options in the treatment of pain associated with endometriosis.

*GnRH antagonists are not yet FDA approved, but may be a potential future treatment.

As previously mentioned, endometriosis is associated with a peritoneal and pelvic inflammatory cascade, and anti-inflammatory compounds may alleviate the pain associated with endometriosis. Since the cyclo-oxygenase-2 pathway is upregulated, COX-2 inhibitors may have a role in treatment, but their main role in treatment of this disease is not well established. Other emerging therapies have targeted the molecular steps involved in endometriosis pathogenesis. This includes agents that enhance cell-mediated immunity, agents that counteract tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), anti-angiogenic agents, metalloproteinase inhibitors, hypocholesterolemic agents, and selective progesterone modulators. A Cochrane Review examined the use of TNF-α inhibitors for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain and found no benefit. (108). Several antiangiogenic agents are in preclinical testing and show promise. Statin medications are also being evaluated as well as trichostatin A and valproic acid (109). These agents are not FDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.

From the available evidence, it is clear that medical treatment is effective for endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. In general, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent alone or in combination with an oral contraceptive agent or a progestin derivative should be considered as first-line therapy. GnRH analogues with add-back therapy and possibly aromatase inhibitors (with oral contraceptive agents, progestins, or a GnRH analog in premenopausal patients), should be regarded as second-line agents. Danazol and gestrinone should be reserved for cases that have failed other medical treatments. If a patient continues to have symptoms of pain despite medical therapy, or needs pain relief but desires pregnancy and thus must avoid hormonal compounds that interfere with ovulation, then conservative surgery should be performed with resection or ablation of lesions and lysis of adhesions. In double-blind randomized control trials, laparoscopic laser treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal-moderate endometriosis was found to decrease pain significantly(109, 111). Follow up re-operation rates after initial surgical removal of lesions was 21%, 47%, and 55% at 2, 5, and 7 years of follow-up, respectively (112). The highest predictor of re-operation was associated with younger age of the patient. The evidence shows that both ablation and resection of lesions are equally effective techniques. Excision of ovarian endometriomas, however, is associated with better pain relief, lower recurrence, and higher pregnancy rates than cyst vaporization or coagulation (113). There is no evidence supporting the performance of a uterosacral nerve ablation; however, if there is significant midline pain, presacral neurectomy may be of benefit (114). It should be noted that presacral neurectomy requires excellent surgical skills, as there is significant risk of damaging the neurovascular plexus or causing retroperitoneal bleeding severe enough to require transfusion or re-operation. Resection of rectovaginal lesions had an approximate 10% complication rate especially when a colorectal resection is performed (115, 116). Good pain relief is usually achieved during the first year after bowel resection for deep endometriosis, but in a systematic literature review, pain recurrence was observed in one out of four patients and re-intervention was required in one out of five of these recurrences (117). A debatable issue is the use of medical therapy, such as a GnRH agonist or medroxyprogesterone acetate, as a neoadjuvant or adjuvant to surgical management. Preoperative medical therapy may be helpful to decrease the pelvic vascularity and size of the endometriotic implants, reducing intraoperative blood loss and surgical resection required. However, by reducing the endometriotic load, the disease may be understaged, which may affect management. Postoperative medical therapy may eradicate the residual implants. A Cochrane Review, however, found insufficient evidence to show a benefit of hormonal suppression either before or after surgery when compared with surgery alone for long-term difference in pain relief from endometriosis (118). There were two trials that compared pre-surgical medical therapy with surgery alone, but American Fertility Society scores were significantly improved in the medical treatment group in one study and not in the other. Post-surgical hormonal suppression of endometriosis versus surgery alone (either no medical therapy or placebo) showed a modest reduction in pain after one year, but results were inconsistent and pain recurrence in both groups indicated no benefit beyond one year after treatment (119). Further, there was no evidence that medical therapy pre- or post-surgery improves pregnancy rates. There have been no trials comparing medical and surgical treatment to reduce endometriosis-associated pain. The studies employing each treatment modality, though, have similar success rates. With this in mind, it is reasonable to conclude that the treatments are equally effective. With the development of newer medical therapies with better tolerated side-effect profiles, surgery may be avoided or delayed. Ultimately, in women who no longer desire future childbearing, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, often is considered as definitive therapy for the treatment. Narcotics should never be considered for treatment of the chronic pain associated with endometriosis. Referral to a multidisciplinary pain center may be of value. In the absence of other factors, if the pain continues to be present after surgery, a diagnosis of adenomyosis should be considered.

Figure 6. Treatment algorithm for pain associated with endometriosis

Infertility

The treatment of infertility, in the absence of pain, may involve expectant management, surgery, ovulation induction/stimulation with intrauterine insemination (IUI), or assisted reproductive techniques, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF). Infertility clinics differ in their use of diagnostic laparoscopy in the evaluation of the etiology of infertility, at which time asymptomatic endometriosis may be diagnosed and excised or ablated. Physicians that do not perform diagnostic laparoscopy as part of their evaluation for infertility would argue that there are significant anesthetic and surgical risks afforded by laparoscopy, ovarian reserve may be compromised by the incidental removal/destruction of normal ovarian tissue, surgery is a cause of adhesions, and that the practice of restoring normal tubal anatomy has fallen out of favor as the success of IVF continues to rise. In women with stage I/II endometriosis, laparoscopic ablation of lesions may offer a small, but significant improvement in live birth rates. A Cochrane Review evaluated two trials in which women were randomized to operative laparoscopy or diagnostic laparoscopy (120). The two randomized trials addressed the question of whether laparoscopic surgery improved outcomes in patients with otherwise unexplained infertility (121, 122). When combining live birth rates and clinical on-going pregnancy rates after 20 weeks, the meta-analysis demonstrated an advantage of laparoscopic surgery when compared to diagnostic laparoscopy alone, with an odds-ratio (OR) of 1.64 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.05-2.57]. However, the two studies had incompatible results, which should be taken into account in this interpretation. One study (121) reported a large positive effect, while the other (122) reported a small negative effect. The number needed to treat, resulting from this analysis, was 12 laparoscopies for one additional pregnancy. The decision to perform surgery should, therefore, be balanced with the patient’s age, history, health status, and wishes, and should be entered into with informed consent about the risks and possible benefits. For those that do undergo surgery, the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI), an intraoperative staging system, can be used to help predict future pregnancy rates. Based on the EFI, a patient may be better counseled regarding her likelihood of spontaneous conception and, if her prognosis is poor, more readily seek appropriate treatment (123). Suppressive medical therapy (such as in the treatment for pain) should not accompany surgery or be involved in the treatment of infertility, as it does not improve fertility and may increase the time to pregnancy. Viable options for the medical treatment of endometriosis-related infertility are discussed. Ovulation induction in women with stage I/II endometriosis confers a fertility benefit. The three randomized trials in the literature addressing this issue, employing either GnRH agonists with follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, clomiphene citrate/IUI, or follicle-stimulating hormone/IUI, all showed increased pregnancy rates relative to the control arm, where the patient did not receive treatment (114). Thus, both ovulation induction plus IUI and assisted reproductive technology have a place in the treatment of women with endometriosis-associated infertility.

If the patient is under the age of 35, initial treatment options include expectant management or controlled ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate or gonadotropins combined with IUI. In a woman over the age of 35, because of the age-associated decrease in fecundity, controlled ovarian stimulation combined with intrauterine insemination or IVF are reasonable therapies. In women with stage III/IV endometriosis, surgery is likely to be of benefit and is recommended by the ASRM Practice Committee, but there are no randomized controlled trials to document efficacy and some studies show a negative effect of surgery on pregnancy rates. (65, 124). Advanced staged disease is often associated with a complex surgical history which, combined with an extensive amount of disease, causes the operation to be difficult, sometimes requiring advanced laparoscopic techniques or laparotomy. These higher acuity surgeries have increased risk of serious complications. In situations when the initial surgery fails to restore fertility, IVF, rather than another operation for infertility, is likely a better option. However, randomized controlled trials are lacking. If surgery is performed, then the subsequent treatment for infertility should be controlled ovarian stimulation (with gonadotropins) and IUI, or IVF, especially in women of advanced reproductive age (66). If the plan is to go directly to IVF, then surgery may not show a benefit, as the slight possible benefit afforded by the surgery is greatly overshadowed by the benefits of IVF and indirect evidence suggests that surgery may not be beneficial in women with deep infiltrating disease (125). There has been some debate about the management of endometriomas in stage IV disease in the absence of pain. Only case series have been published, but the overall likelihood of pregnancy following endometrioma excision is around 50% (125); though this may be an overestimate with women achieving pregnancy through IVF.

The question then remains, should the endometriomas be removed prior to IVF? A meta-analysis evaluated five studies that compared surgery versus no treatment for an endometrioma (121). In this analysis, there were no differences in the pregnancy rates or responses to controlled ovarian stimulation in the two groups, favoring against surgical resection. There are no randomized controlled trials that evaluate this question. Surgery for endometriomas should be performed to relieve pain and to confirm the diagnosis in situations when it is in question. Overall, endometriosis is a common indication for IVF. IVF allows the abnormal anatomy to be overcome by avoiding the tubes; the oocyte is retrieved directly from the ovaries, and the embryos are placed directly in the endometrial cavity, thereby bypassing the effects of the abnormal peritoneal environment. Despite this, endometriosis is associated with overall lower chances of success. This may be due to the negative impact of endometriosis on folliculogenesis and endometrial receptivity (126). A meta-analysis demonstrated significantly lower pregnancy rates for women with endometriosis compared to women with tubal factor infertility controls. Pregnancy rates were also significantly lower for women with severe endometriosis versus women with milder disease (127). However, the difference in pregnancy rates does not appear to be attributable to differing aneuploidy rates. A recent retrospective cohort study demonstrated no difference in aneuploidy rates between age-matched controls of women with endometriosis undergoing IVF compared to those without endometriosis (128).

Figure 7. Treatment algorithm for infertility associated with endometriosis.

Other Therapeutic Modalities

There have been many studies exploring complementary alternative medicine (CAM) for the treatment of symptoms associated with endometriosis. Although these approaches are not FDA or USDA approved for the treatment of endometriosis, they may offer relief by suppressing cytokines and inflammatory pathways, inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) pathways, acting as antioxidants, and alleviating pain by other mechanisms (129). High frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, acupuncture, vitamin B1, magnesium, reflexology, traditional Chinese medicine, herbal treatments, and homeopathy are examples of CAM that have been explored for use in endometriosis-associated pain. Even though the risks associated with some of these modalities appear minimal, the standards of evidence-based medicine on aspects of safety and efficacy have not been applied to most studies involving CAM. A promising note for CAM is that there is now a National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Hopefully, this will allow for proper evidence-based evaluation, so that their safety and efficacy can be compared with the more traditional approaches (129). Another therapeutic modality that may be considered is patient self-help and support groups. Information can be found at www.endometriosis.org (76).

ENDOMETRIOSIS-ASSOCIATED OVARIAN CANCER

Although it is not considered a pre-malignant condition, there are data to suggest that endometriosis has neoplastic potential (130). Endometriosis shares several similarities with malignant diseases such as reduced apoptosis, invasion of endometrial cells into adjacent organs (bowel, bladder), increased angiogenesis, ability to spread distantly, etc. (131-133). Women with endometriosis have twice the risk of developing epithelial ovarian cancer compared to controls, and a 4-fold increased risk if they also have subfertility (134). The association is limited to clear cell (OR 3.05, 95% CI 2.43-3.84), endometroid (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.67-2.48), and low-grade serous (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.39-3.2) tumors (135). The carcinogenic pathways, however, poorly understood. There is thought that oxidative stress, inflammation and the estrogen dependent environment may play a role (136). In women without malignant appearing features on ultrasound, 1-3% are found to have atypical endometriotic cells (125). Generally, endometriosis associated malignancies arise from endometriomas. Reactive oxygen species generated by catalytic iron from phagocytosed heme causes cell damage, DNA mutations, and genetic instability may be aided by the local ovarian environment of endometriomas (137-139). This oxidative stress is thought to activate proto-oncogenes or disrupt tumor suppressor genes, such as ARID1A (140-142). Clear cell and endometroid tumors also develop due to hormonally dependent and independent pathways. Endometroid cell types are often estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptor positive. Clear cell tumors, however, generally have low receptor expression (143). Endometroid histology is also thought to be estrogen-dependent based on the fact that there is a higher than expected rate of synchronous primary, estrogen-dependent endometrial endometroid carcinoma (144) concurrently with endometriosis-associated ovarian endometroid carcinoma. (145-147). Clear cell carcinomas overexpress hepatocyte nuclear factor 1ß, which is a transcriptional factor that increases survival of endometrial cells during oxidative stress by inhibiting apoptosis, whereas endometroid cell types do not overexpress hepatocyte nuclear factor 1ß (137). Knowing the increased risk of carcinoma in endometriosis patients, the question remains as to how to prevent progression. There are limited data available regarding medical and surgical interventions for prevention. It is known that oral contraceptives are associated with an 80% reduction in risk among women with endometriosis when used for greater than 10 years. Since endometroid subtypes are ER and PR positive, whereas clear cell subtypes are not, those at risk for the endometroid subtype are more likely to benefit from hormonal therapy while those more likely to develop the clear cell subtype would benefit from surgery. In Western countries the endometroid subtype is more prevalent than clear cell, 10-20% versus 5-10%, respectively. However, the opposite is true in Asian countries. This could suggest a population based treatment approach (144-146).

CONCLUSION

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease, the pathophysiology of which we are just beginning to understand. Symptomatic women with endometriosis, suffering from infertility or pain, are often difficult patients to treat because we have few treatment options to offer. The therapies themselves are imperfect, with none that permanently eradicate the disease. A multidisciplinary approach is often required for the diagnosis and management of this disease. In deciding how to treat women with pelvic pain or infertility, we must consider the best available evidence to form our decisions. In women with pelvic pain and suspected endometriosis, first line treatment would be non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications with/without oral contraceptives or progestins. Continuous combined oral contraceptives have been shown to provide significant pain reduction from baseline over cyclic combined oral contraceptives(148). If these conservative approaches fail, three alternative treatments would be empiric: GnRH agonist therapy with estrogen and progestin add-back therapy, aromatase inhibitors, or operative laparoscopy. The laparoscopy should include lysis of adhesions and excision or ablation of endometriosis. Surgery for pain may be followed by medical treatment with GnRH agonist and add-back therapy (Fig. 6). It is important to note that at no time are narcotics advocated for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain except immediately pre-operatively or post-operatively. If the above measures fail, patients should be enrolled into a multi-disciplinary chronic pelvic pain treatment group. This should include physicians from many subspecialties, including psychiatry, anesthesiology, gynecology, and often gastroenterology and urology.

REFERENCES

- Gustofson, RL, Kim, N, Liu, S, Stratton, P. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril 2006; 86:298.

- Bulun, Serdar E. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:268-278.

- Hsu, Albert, L., Khachikyan, Izabella, and Stratton, Pamela. Invasive and noninvasive methods for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010; 53:413-419.

- Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1927; 14:422-69.

- Olive DL, Schwartz LB. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:1759-69.

- Olive, DL, Henderson, DY. Endometriosis and Mullerian anomalies. Obstet Gynecol 1987; 69:412.

- Blumenkrantz JM, Gallagher N, Bashore RA, Tenckhoff, H. Retrograde menstruation in women undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis. Obstet Gynecol 1981; 57:667-70.

- Kruitwagen RF, Poels LG, Willemsen WN, de Ronde IJ, Jap PH, Rolland R. Endometrial epithelial cells in peritoneal fluid during the early follicular phase. Fertil Steril 1991; 55:297-303.

- Meyer R. Uber den staude der frage der adenomyosites adenomyoma in allgemeinen und adenomyometritis sarcomastosa. Zentralb Gynakol 1919; 36:745.

- Gebel HM, Braun DP, Tambur A, Frame D, Rana N, Dmowski WP. Spontaneous apoptosis of tissue is impaired in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1998; 69:1042-4.

- Evers JLH. The defense against endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1996; 66:351-3.

- Witz CA, Montoya-Rodriguez IA, Miller DM, Schneider BG, Schenken RS. Mesothelium expression of integrins in vivo and in vitro. J Soc Gynecol Invest 1998; 5:87-93.

- Osteen KG, Bruner KL, Sharpe-Timms KL. Steroid and growth factor regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression and endometriosis. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1996; 14:247-55.

- Taylor RN, Ryan IP, Moore ES, Hornung D, Shifren JL, Tseng JF. Angiogensis and macrophage activation in endometriosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1997; 828:194-207.

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2001; 75:1-10.

- Gupta S, Goldberg JM, Aziz N, Goldberg E, Krajcir N, Agarwal A. Pathogenic mechanisms in endometriosis associated infertility. Fertil Steril 2008; 90:247-257.

- Jackson LW, Schisterman EF, Dey-Rao R, et al. Oxidative stress and endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005; 20:2014–20.

- Somigliana E, Panina-Bordignon P, Murone S, et al. Vitamin D reserve is higher in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2007; 22:2273–8.

- Vigano P, Lattuada D, Mangioni S, et al. Cycling and early pregnant endometrium as a site of regulated expression of the vitamin D system. J Mol Endocrinol 2006; 36:415–24.

- McLaren J, Prentice A, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is produced by peritoneal fluid macrophages in endometriosis and is regulated by ovarian steroids. J Clin Invest 1996; 98:482–9.

- Sayegh L, Fuleihan GE, Nassar AH. Vitamin D in endometriosis: A causative or confounding factor? Metabolism Clinical and Experimental. 63 (2014) 32–41.

- Bulun SE, Monsavais D, Pavone ME, Dyson M, Xue Q, Attar E, Tokunaga H, Su EJ. Role of estrogen receptor-β in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2012 Jan; 30(1):39-45.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 160:784.

- Hediger, ML, Hartnett, HJ, Louis, GM. Association of endometriosis with body size and figure. Fertil Steril 2005; 84:1366.

- Malinak LR, Buttram VC Jr, Elias S, Simpson JL. Heritage aspects of endometriosis. II. Clinical characteristics of familial endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1980; 137:332–7.

- Matalliotakis IM, Arici A, Cakmak H, Goumenou AG, Koumantakis G, Mahutte NG. Familial aggregation of endometriosis in the Yale Series. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008; 278:507–11.

- Nyholt DR, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2012 Dec; 44(12):1355-9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2445. Epub 2012 Oct 28.

- Pagliardini L, Gentilini D, Vigano' P, Panina-Bordignon P, Busacca M, Candiani M, Di Blasio AM. An Italian association study and meta-analysis with previous GWAS confirm WNT4, CDKN2BAS and FN1 as the first identified susceptibility loci for endometriosis. J Med Genet. 2013 Jan; 50(1):43-6. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101257.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Malspeis S, Willett WC, Hunter DJ. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104:965.

- Balasch J, Creus M, Fabregues F, Carmona F, Ordi J, Martinez-Roman S, et al. Visible and non-visible endometriosis at laparoscopy in fertile and infertile women and in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a prospective study. Hum Reprod 1996; 11:387–91.

- Rawson JM. Prevalence of endometriosis in asymptomatic women. J Reprod Med 1991; 36:513–5.

- Strathy JH, Molgaard CA, Coulam CB, Melton LJ 3rd. Endometriosis and infertility: a laparoscopic study of endometriosis among fertile and infertile women. Fertil Steril 1982; 38:667–72.

- Verkauf BS. Incidence, symptoms, and signs of endometriosis in fertile and infertile women. J Fla Med Assoc 1987; 74:671–5.

- Carter JE. Combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic findings in patients with chronic pelvic pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1994; 2:43–7.

- Koninckx PR, Meuleman C, Demeyere S, Lesaffre E, Cornillie FJ. Suggestive evidence that pelvic endometrio- sis is a progressive disease, whereas deeply infiltrating endometriosis is associated with pelvic pain. Fertil Steril 1991; 55:759–65.

- Ling FW. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Pelvic Pain Study Group. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 93:51–8.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Hysterectomies in the United States, 1965-84. Hyattsville, MD. National Center for Health Statistics, 1987(Vital and Health Statistics, Series 13, Data from the National Health Survey, No. 92, DHHS Publ No. (PHS. 88-1753).

- Rier SE, Martin DC, Bowman RE, Dmowski WP, Becker JL. Endometriosis in rhesus monkeys (macaca mulatta. following chronic exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Fund Applied Toxicol 1993; 21:433-41.

- Signorile PG, Spugnini EP, Mita L, Mellone P, D'Avino A, Bianco M, Diano N, Caputo L, Rea F, Viceconte R, Portaccio M, Viggiano E, Citro G, Pierantoni R, Sica V, Vincenzi B, Mita DG, Baldi F, Baldi A. Prenatal exposure of mice to bisphenol A elicits an endometriosis- like phenotype in female offspring. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2010.

- Parazzini F, Cipriani S, Bravi F, Pelucchi C, Chiaffarino F, Ricci E, Viganò P. A meta analysis on alcohol consumption and risk of endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013 209; 106.e1–10.

- Noble, L. S., Simpson, E. R., Johns, A. & Bulun, S. E. Aromatase expression in endometriosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996; 81, 174–179.

- Buck Louis GM, Peterson CM, Chen Z, Croughan M, Sundaram R, Stanford J, Varner MW, Kennedy A, Giudice L, Fujimoto VY, Sun L, Wang L, Guo Y, Kannan K. Bisphenol A and phthalates and endometriosis: the Endometriosis: Natural History, Diagnosis and Outcomes Study. Fertil Steril 2013; 100:162–9.

- M., Mesrine. S., Clavel-Chapel, F. & Boutron-Ruault, M. C. Endometriosis risk in relation to naevi, freckles and skin sensitivity to sun exposure: the French E3N cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009; 38, 1143–1153.

- Somigliana E, Viganò P, Abbiati A, Gentilini D, Parazzini F, Benaglia L, Vercellini P, Fedele L. ‘Here comes the sun’: pigmentary traits and sun habits in women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2010; 25, 728–733.

- Vitonis, A. F., Hankinson, S. E., Hornstein, M. D. & Missmer, S. A. Adult physical activity and endometriosis risk. Epidemiology 2010; 21, 16–23.

- Viganò P, Somigliana E, Panina P, Rabellotti E, Vercellini P, Candiani M. Principles of phenomics in endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2012; 18, 248–259.

- Lafay Pillet MC, Schneider A, Borghese B, Santulli P, Souza C, Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Chapron C. Deep infiltrating endometriosis is associated with markedly lower body mass index: a 476 case–control study. Hum. Reprod. 2012; 27, 265–272.

- Shah, D. K., Correia, K. F., Vitonis, A. F. & Missmer, S. A. Body size and endometriosis: results from 20 years of follow-up within the Nurses’ Health Study II prospective cohort. Hum. Reprod. 2013; 28, 1783–1792.

- Vercellini, P. Endometriosis: What a pain it is. Semin. Reprod. Endocrinol. 1997; 15, 251–261.

- Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis on 1000 patients. Hum. Reprod. 2007; 22, 266–271.

- Ballard, K. D., Seaman, H. E., de Vries, C. S. & Wright, J. T. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case–control study—Part 1. BJOG 2008; 115, 1382–1391.

- Olive DL, Blackwell RE, Copperman AB. Endometriosis and pelvic pain. In: Blackwell RE, Olive DL, editors. Chronic Pelvic Pain: Evaluation and Management. Springer, New York, 1997; pgs 61-83.

- Bokor, Xinmei, Yao, Huijiao, Huang, Xiufeng, Lu, Bangchun, Xu, Hing, and Zhou, Caiyun. Nerve fibres in ovarian endometriotic lesions in women with ovarian endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2010; 25:392-397.

- Al-Jefout, M, Dezarnaulds, G, Cooper, M, Tokushige N, Luscombe GM, Markham R, Fraser IS. Diagnosis of endometriosis by detection of nerve fibres in an endometrial biopsy: a double blind study. Hum Reprod. 2009; 24:3019-3024.

- Bokor, A, Kyama, CM, Vercruysse, L, Fassbender A, Gevaert O, Vodolazkaia A, De Moor B, Fülöp V, D'Hooghe T. Density of small diameter sensory nerve fibres in endometrium: a semi-invasive diagnostic test for minimal to mild endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009; 24:3025-3032.

- Anaf V, Simon P, El Nakadi I, Fayt I, Buxant F, Simonart T, Peny MO, Noel JC. Relationship between endometriotic foci and nerves in rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum Reprod 2000; 15:1744.

- Wang, G, Tokushige, N, Markham, R, Fraser, IS. Rich innervation of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2009; 24:827.

- Howard, F. M. Endometriosis and mechanisms of pelvic pain. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009; 16, 540–550.

- Bajaj,P., Bajaj,P., Madsen,H. & Arendt- Nielsen, L. Endometriosis is associated with central sensitization: a psychophysical controlled study. J. Pain 2003; 4, 372–380.

- Berkley, K. J., Rapkin, A. J. & Papka, R. E. The pains of endometriosis. Science 2005; 308, 1587–1589.

- Stratton, P. & Berkley, K. J. Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum. Reprod. Update 2011; 17, 327–346.

- Tran, Lu Vinh Phuc, Tokushige, Natusuko, Berbic, Marina, Markham, Robert, and Fraser, Ian. Macrophages and nerve fibres in peritoneal endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009; 24:835-841.

- Guzick DS, Silliman NP, Adamson GD, Buttram VC Jr, Canis M, Malinak LR, Schenken RS. Prediction of pregnancy in infertile women based on the American Society for Reproductive Medicine's revised classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1997; 67:822-829.

- Inoue M, Kobayashi Y, Honda I, Awaji H, Fujii A. The impact of endometriosis on the reproductive outcome of infertile patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 167:278-282.

- The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis and Infertility. Fertil Steril 2006; 86:S156-S160.

- Cahill, DJ. What is the optimal medical management of infertility and minor endometriosis?: Analysis and future prospects. Hum Reprod 2002; 17:1135.

- Isaacson KB, Galman M, Coutifaris C, Lyttle CR. Endometrial synthesis and secretion of complement component-3 by patients with and without endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1990; 53:836-41.

- Tseng JF, Ryan IP, Milam TD, Murai JT, Schriock ED, Landers DV, Taylor RN. In terleukin-6 secretion in vitro is up-regulated in ectopic and eutopic endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:1118-1122.

- Taylor HS, Bagot C, Kardana A, Olive DL, Arici A. HOX gene expression is altered in the endometrium of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 1999; 14:1328-31.

- Lessey BA, Young SL. Integrins and other cellular adhesion molecules in endometrium and endometriosis. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1997; 15:291-9.

- Sinaii, N, Cleary, SD, Ballweg, ML, Nieman, LK, and Stratton, P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Repro 2002; 17:2715-2724.

- Contemporary Concepts in Clinical Management. Schenken RS, editor. J.B.Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, 1989.

- Lundberg W, Wall J, Mathers J. Laparoscopy in evaluation of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol 1973; 42:872-76.

- Diamond M, Daniell J, Johns D, et al. Postoperative adhesion development after operative laparoscopy: evaluation at early second look procedures. Fertil Steril 1991; 55:700-4.

- Hoyos L, Johnson S, Puscheck E. Endometriosis and Imaging. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2017; 60:503-516.

- Kennedy S, Bergqvist A, Chapron C, D'Hooghe T, Dunselman G, Greb R, Hummelshoj L, Prentice A, Saridogan E; ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005; 20:2698-2704.

- Hudelist G, Tuttlies F, Rauter G, Pucher S, Keckstein J. Can transvaginal sonography predict infiltration depth in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum? Hum Reprod 2009; 24:1012.

- Bazot M, Malzy P, Cortez A, Roseau G, Amouyal P, Daraï E. Accuracy of transvaginal sonography and rectal endoscopic sonography in the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 30:994.

- Faccioli N, Manfredi R, Mainardi P, Dalla Chiara E, Spoto E, Minelli L, Mucelli RP. Barium enema evaluation of colonic involvement in endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190:1050.

- Piketty M, Chopin N, Dousset B, Millischer-Bellaische AE, Roseau G, Leconte M, Borghese B, Chapron C. Preoperative work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis: transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line imaging examination. Hum Reprod 2009; 24:602.

- Hudelist G, Oberwinkler KH, Singer CF, Tuttlies F, Rauter G, Ritter O, Keckstein J. Combination of transvaginal sonography and clinical examination for preoperative diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2009; 24:1018.

- Bazot M, Lafont C, Rouzier R, Roseau G, Thomassin-Naggara I, Daraï E. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, transvaginal sonography, rectal endoscopic sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2009; 92:1825.

- Arrive L, Hricak H, Martin MC. Pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging. Radiology 1989; 171:687.

- 83 Togashi K, Nishimura K, Kimura I, Tsuda Y, Yamashita K, Shibata T, Nakano Y, Konishi J, Konishi I, Mori T. Endometrial cysts: diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 1991; 180:73.

- Mawhinney RR, Powell MC, Worthington BS, Symonds EM. Magnetic resonance imaging of benign ovarian masses. Br J Radiol 1988; 61:179.

- Woodward PJ, Gilfeather M. Magnetic resonance imaging of the female pelvis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 1998; 19:90-103.

- Pittaway DE, Fayez JA. The use of CA-125 in the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1986; 46:790.

- Zhang X, Lu B, Huang X, Xu H, Zhou C, Lin J. Endometrial nerve fibers in women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, and uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril 2009; 92:1799 – 1801.

- Zhang X, Lu B, Huang X, Xu H, Zhou C, Lin J. Innervation of endometrium and myometrium in women with painful adenomyosis and uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril 2010; 94:730– 737.